"The performance of the NHS continues to decline, while demands on the service from Scotland's ageing population are growing. The scale of the challenges facing the NHS means that decisive action is needed now to deliver the fundamental change that will secure the future of this vital and valued service.”

If this was said by a politician it would be dismissed as political rhetoric. In fact, it was said by Caroline Gardner, Auditor General for Scotland, when launching this year’s overview of NHS Scotland. The report does not make happy reading and ought to be a huge wake up call.

The main message is that the NHS in Scotland is not in a financially sustainable position. NHS boards are struggling to break even, relying increasingly on Scottish Government loans and one-off savings. The report was prepared before the Health Secretary accepted this reality and announced that these loans were to be written off.

Health boards did achieve an unprecedented £449m of ‘savings’, but many of these are one off savings and that is not sustainable. In 2017/18, 50% of all savings were one-off (non-recurring), up from 35% in 2016/17, and 20% in 2013/14. In 2018/19, eight boards predicted at the start of the year that they would be in deficit at the end of the year.

Although health funding has increased over the past decade, funding per head of population has increased at a slower rate. We should also remember that ‘real terms’ is based on the government’s optimistic view of inflation, which has little basis in reality for the economy as a whole, let alone higher health inflation rates.

The financial position is unlikely to improve soon as health costs are projected to increase. Scotland’s ageing population means that more people will be living longer with multiple long- term conditions. Other cost pressures, such as increases in drug spending, are also projected to intensify and there is a significant maintenance backlog. Some progress has been made in reducing agency staff and medical locums, but they have still increased by nearly 40% in the last five years.

There is a medium-term health and social care financial framework, but the auditors are as unclear as everyone else how this relates to the government’s financial strategy. This was part of the analysis recently published by John McLaren and highlighted in Brian Wilson’s Scotsman column. In particular, this analysis shows that Scotland is expecting to make double the efficiency savings than in England.

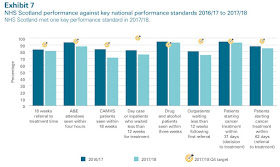

The report also highlights declining performance. The NHS met only one of eight key national performance targets in 2017/18, and performance actually declined against all eight. No board met all eight targets. NHS Lothian did not meet any targets. NHS Grampian, Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Highland, and Tayside each met one target.

In the final quarter of 2017/18, 93,107 people waited more than 12 weeks for their first outpatient appointment, an increase of 6% on the previous year. The number of people who waited more than 12 weeks has increased by 215% in the last five years. People waiting more than 16 weeks increased by 16% last year, and by 558% over the last five years. People waiting more than 12 weeks for an inpatient or day case procedure increased by 26% last year to 16,772 people, and by 544% over the last five years.

Those who do receive treatment continue to rate their care and the staff who deliver it highly. Staffing levels are at their highest level, but vacancies remain high, particularly long-term vacancies. Huge challenges are on the horizon, including Brexit. Sickness absence has increased and nearly half of staff report in the staff survey that they couldn’t meet all the conflicting demands on them.

As always with these reports, the analysis of where we are is stronger than the solutions. Auditors like process and the report recommends a number of changes to these. In fairness, it is not the Audit Scotland’s job to address the challenges – it is the Health Secretary who has to lead on this. And, as they say, any solution has to start with an understanding of the challenges.

In financial terms, much will depend on the Scottish Government receiving additional funding from the Barnett consequentials of English health spending. However, this report rightly warns that we don’t yet how the UK Government plans to fund increases in English health expenditure and the options chosen may affect the amount available to the Scottish Government.

The report also highlights the number of leadership vacancies, joint posts and confused governance. We have new layers of planning, but it is unclear what progress is being made. The limited training, skills and performance management of non-executive board members are highlighted as a concern in the report. There was a review of targets and indicators last year, but no progress on the recommendations.

The report highlights slow progress in health and care integration while recognising the challenges. It welcomes the workforce planning initiatives, but recognises that these describe processes, not what the medium to long-term workforce will actually look like.

We should not forget the underlying causes of many of the pressures on the NHS – health inequalities. We had another warning on this today in the EHRC report ‘Is Scotland Fairer?’. Sadly, this probably won’t get as much consideration as the Audit Scotland report, but it is crucial to understanding the pressures on our NHS. The report highlighted differences in educational attainment, health, work opportunities and living standards among social groups and concluded that progress has stagnated.

In summary, this report pulls together many of the warning signs that have been around for some time. Nothing in the Audit Scotland report should detract from the great outcomes that NHS Scotland staff deliver every day in difficult circumstances. Neither do they indicate that the system is fundamentally flawed. However, the report does lay bare the challenges facing NHS Scotland and the focus should be on real action to address them and the underlying causes of poor health.

In summary, this report pulls together many of the warning signs that have been around for some time. Nothing in the Audit Scotland report should detract from the great outcomes that NHS Scotland staff deliver every day in difficult circumstances. Neither do they indicate that the system is fundamentally flawed. However, the report does lay bare the challenges facing NHS Scotland and the focus should be on real action to address them and the underlying causes of poor health.