Poor mental health affects half of all employees, but only half of those who experience problems talk to their employer about it.

I have been working with an employer on improving their approach to tackling mental health in the workplace. Their sickness absence statistics highlighted a growing problem and a management consultant produced a plan. The safe response from many Chief Executive's would be to tick the box and report the action taken to the board. Credit to this organisation that they didn't do that. The CEO wasn't convinced that the actions proposed would tackle the scale of the problem and asked me to review the plan.

The hard-nosed case for taking real action is economic, with mental ill health-related absences costing at least £26 billion per year. However, the human cost is even greater for the sufferer and their families, with the ultimate human cost being loss of life through suicide.

In some ways, the increase in reported mental health absence is a positive sign that the stigma is reducing. A British Chambers of Commerce survey showed a 30% increase in the last three years and a 33% increase in the length of absences. Even in NHS Scotland, between 2015/16 and 2017/18, the number of stress-led staff absences has rocketed by 17.6% - the equivalent of more than one million working days lost.

However, another survey undertaken by BHSF indicated that 42% of UK employees who have called in sick and claimed they were physically unwell were actually covering up a mental health issue. Another estimate by the ‘Time to Change Employer Pledge’ says, 95% of employees calling in sick with stress gave a different reason.

It’s not just absence either. Surveys show that poor mental health affects performance in the workplace including concentration, decision making, avoiding certain tasks and conflict with colleagues and customers.

Given the moral and economic case for acting, what should employers and unions do?

The plan I reviewed had a number of worthy elements. There was some awareness training for managers, but not for front-line staff. They also planned to deliver mindfulness events and relaxation sessions. The fundamental problem was that the plan largely ignored work as a factor in poor mental health. The focus was on individual behaviour and health, rather than looking at the impact the employer was having on mental health. In other words, it was a reactive rather than a preventative approach to mental health at work.

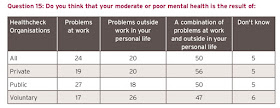

Most poor mental health is the result of a combination of problems at work and personal life, with work alone causing problems for a quarter of staff. While most staff recognise they have to address their mental health problems, they need a supportive work environment with well-trained line managers and an organisational response.

The positive news is that the issue is getting much greater attention and there are a range of resources to help employers. The ‘Time to Change Employer Pledge’ encourages a health check and sharing best practice across a growing number of employers - although some argue this doesn't go far enough. The CIPD has a number of useful guides as well as survey data. They broaden the issue to address ‘well-being’ at work. The mental health charity Mind has a range of resources and can help with training. Trade unions, including UNISON and Unite, run awareness or mental health first-aid courses for their stewards. UNISON also has a useful bargaining guide.

The employer I have been working with now has a comprehensive mental health at work plan, which starts with clear objectives that form part of the organisation’s strategy, not simply an HR add-on. It shows how they will identify the well-being of staff and the causes of poor mental health in the workplace. Then the measures they are taking to tackle the work-related causes and the support available inside and outside the organisation. Finally, how the plan will be evaluated.

We should also not forget the wider policy imperative to address poor mental health. As TUC research points out, while employment rates of disabled people with mental health problems have increased, they are still at very low levels. The economy cannot afford to miss out on the skills and talents of these people.

Taking serious action to tackle mental health issues in the workplace requires more than a few cosmetic initiatives. The good news is that more employers and trade unions recognise the problem and are prepared to take meaningful action to effect change.

No comments:

Post a Comment